We evolved from animals whose survival depended on making quick decisions with limited information. Our ancestors had to recognize threats instantly. Only those who mastered detecting predators' eyes in the thick grass or behind the trees survived and passed their genes to the next generation. Today, their descendants can enjoy "the talent" of seeing faces in textures or random objects. The once life-saving skill seems now like a funny quirk of the mind called pareidolia.

We're also social animals whose success in a group relies on recognizing emotions through deciphering facial expressions. Information gathered from faces helps us understand what others are thinking and feeling. We can project the ability of facial perception on non-human objects as well. We readily perceive two dots and a line as a face and even interpret it as expressing a particular emotion — happiness, anger, pain.

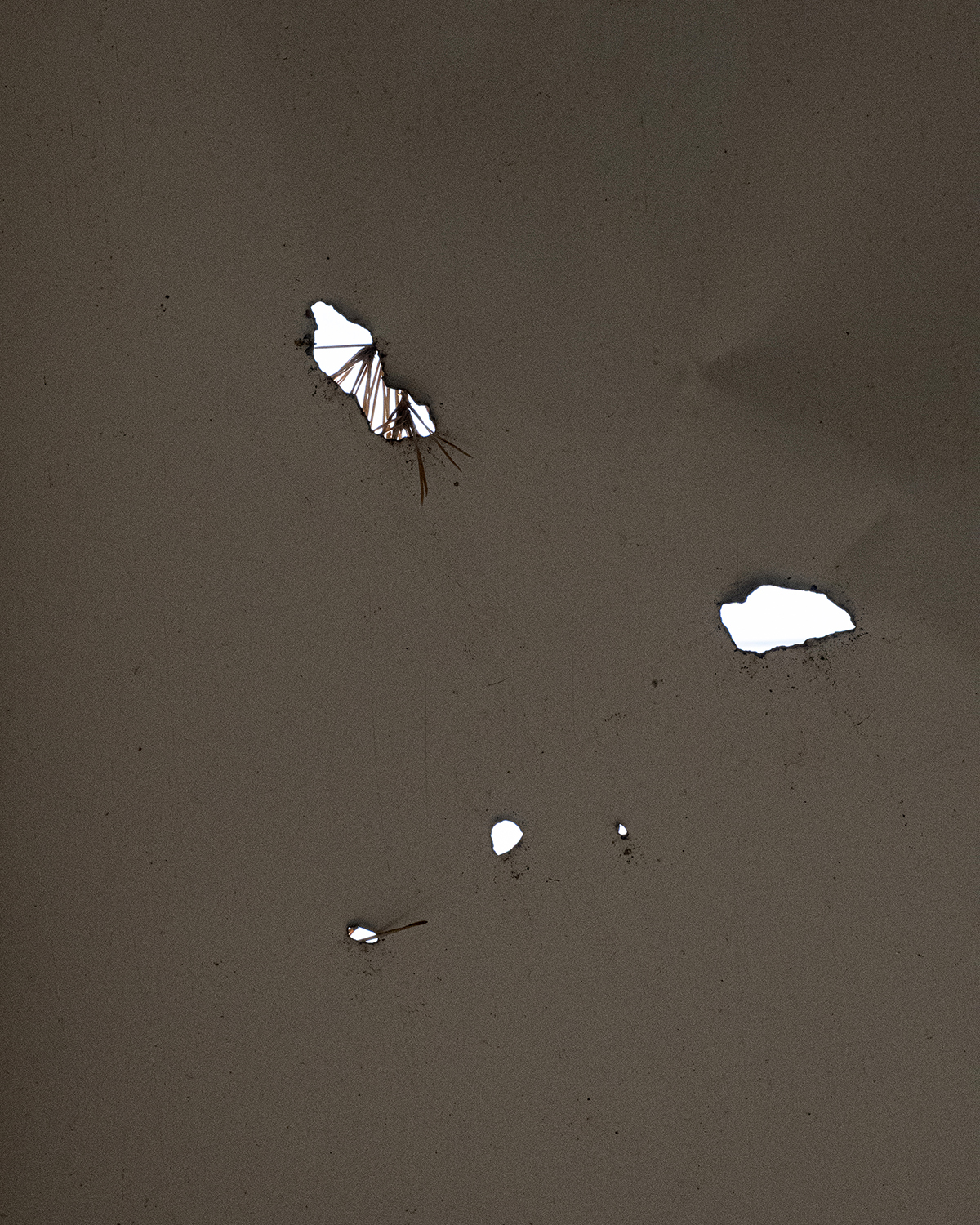

When Russians fled from the Kyiv region, I went to Irpin, a city next to Bucha, to photograph the traces of the invasion. I instantly felt I had trouble approaching people who witnessed the battle and occupation. I couldn't talk or point a camera at anyone. Still, I felt an urgent need to document, so I just walked down the streets in an attempt to find less visible, metaphorical signs of the war. I took a closer look at the surfaces of the city that suffered from bomb explosions and noticed pareidolic faces formed by shrapnel holes. They seemed like new inhabitants of the once-occupied and now-liberated town. Shooting their portraits has become my way of showing the consequences of the war without intruding on others' personal space.